Remembering Bill Russell

by Chris Albertson

In my recollections of the 1961 New Orleans “Living Legends” trip, I mention William Russell, the man who was, in good measure, responsible for a 1940s awakening that is often referred to as the “New Orleans Jazz Revival.” His bringing trumpeter Bunk Johnson out of an Iberia rice field, buying him a horn and refurnishing his mouth may be apocryphal, but it is still being told some seven decades later. While the revival, per se, was fairly short-lived, it laid the groundwork for the “trad” movement in Europe and eventually morphed into that which sparked the British invasion—Animals, Beatles, Stones…you get the idea.

Bill was a month away from his 65th birthday when I first met him, but he looked older and acted older still. I was in New Orleans to make recordings of the music he loved and almost considered proprietary, so I expected him to pop up, which he did. Had he not, it was on my do list to look him up. On the first recordings I ever made, about 12 years earlier, I captured a Jacinto Hall-like ambiance at the Gentofte Hotel, in a Copenhagen suburb. The band on that occasion was Ken Colyer’s Jazzmen, a group that took to Bill Russell’s recordings like bees to nectar. In fact, there would not have been a band like Colyer’s (actually Chris Barber’s with Ken up front) were it not for the sessions Bill issued on his American Music label.

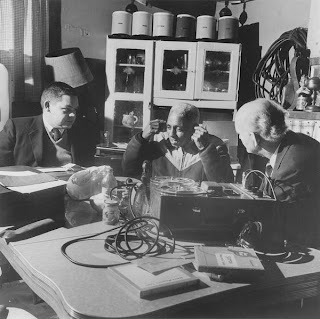

Bill and Dick Allen (pictured here conducting an interview) documented much New Orleans jazz history for the Tulane Jazz Archives. Unfortunately, some of those tapes may have been “censored” (see something on that here, starting with the 7th paragraph). I hope I am wrong. Nevertheless, I was delighted to meet this man whose work had so impressed me. When I learned that he owned a small record shop nearby, I asked if he had any of his American Music recordings available. Not for the public, he said, but you are welcome.

During a rare moment of leisure that week, I went to visit Bill at his shop. It was as I had imagined it, full of abundant local sounds, a bit cluttered, and very warm or, as we say in Denmark, “hyggelig”. There is no word in the English language that quite covers the meaning of hyggelig—”cozy” is halfway there, but only half way. Let’s just say that the shop had an inviting, lived-in look and that Bill was very much a part of his surroundings. No, he had an apartment elsewhere in the Quarter, but one sensed that this was as much a home to him as any other might be.

My opening the door activated a tinkly bell. Bill, crouched, Geppetto-like, over something that obviously had his full attention, looked over his glasses, recognized me instantly, pushed away a large mounted magnifying glass, and gave me a welcoming smile. He had been repairing a violin, which, as I soon discovered, was just another of his many talents.

The one-room shop almost begged one to look around, so I instinctively complied, spotting a row of violins hanging from the ceiling, and a large single-occupancy bird cage suspended nearby.

Bill and I had just started a conversation when he asked if I was still interested in the American Music albums. Of course I was, so he disappeared into a back room and returned with three discs in the familiar pink and green cardboard sleeves. “This is all I have left,” he said, and if you want them, you will have to give me some time to fix them.”

Fix them? I didn’t know what he meant by that, but it turned out that his remaining stock of discs had tiny vinyl bumps that needed to be filed down before he let anyone have them. Then he pushed away the violin and began to meticulously file away bumps so small that I couldn’t see them. This took a couple of hours, but our conversation made the time seem shorter. Bill also gave me permission to peruse his vast collection of historic New Orleans post cards. They were not for sale, he told me, but it was one of his hobbies.

While Bill filed away and I gently leafed through rows of fascinating cards, the bell tinkled again. A typical white, middle-aged tourist couple entered the store. They were in love with the city and wanted to take some of the great music back home with them. Bill did not get up, he just gestured toward the record bins with his file and told them to pick out what they wanted.

They finally found something, but when Bill saw the Dukes of Dixieland album in the man’s hands, he told him that this one was not for sale. “But it was in the bin,” the startled man said. “I know,” said Bill, as he stood up, “but it’s not for sale.” Then he walked over to the bins and extracted a Bunk Johnson album, the one on Columbia. “Here, take this one,” he said, “it’s much better and it’s free.”

The couple were speechless as they left the store with their free album. I had to smile, for I knew what that was all about.

Bill sat down and continued his de-bumping.

Bill Russell (far right) played regularly with the New Orleans Ragtime Band.

Comment made on article:

I first met Bill Russell in 1958. Used to congregate at his shop (which was a kind of HQ) with Herb Friedwald, Lee Friedlander, Dick Allen and various others. I saw a lot of him over the ensuing years and he, together with Dick and Herb became close friends. I miss ’em all.

I brought the NO Ragtime Orch. over on a tour of Europe in 1973 and miss all of the other members who have passed as well.

Best Regards,

Mike Casimir

Source: http://stomp-off.blogspot.com/2010/01/eccentric-side-of-william-russell.html

Leave a Reply